When US president Joe Biden meets with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in the San Francisco Bay Area this week, the pair will have a long list of matters to discuss, including the Israel-Hamas war and Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

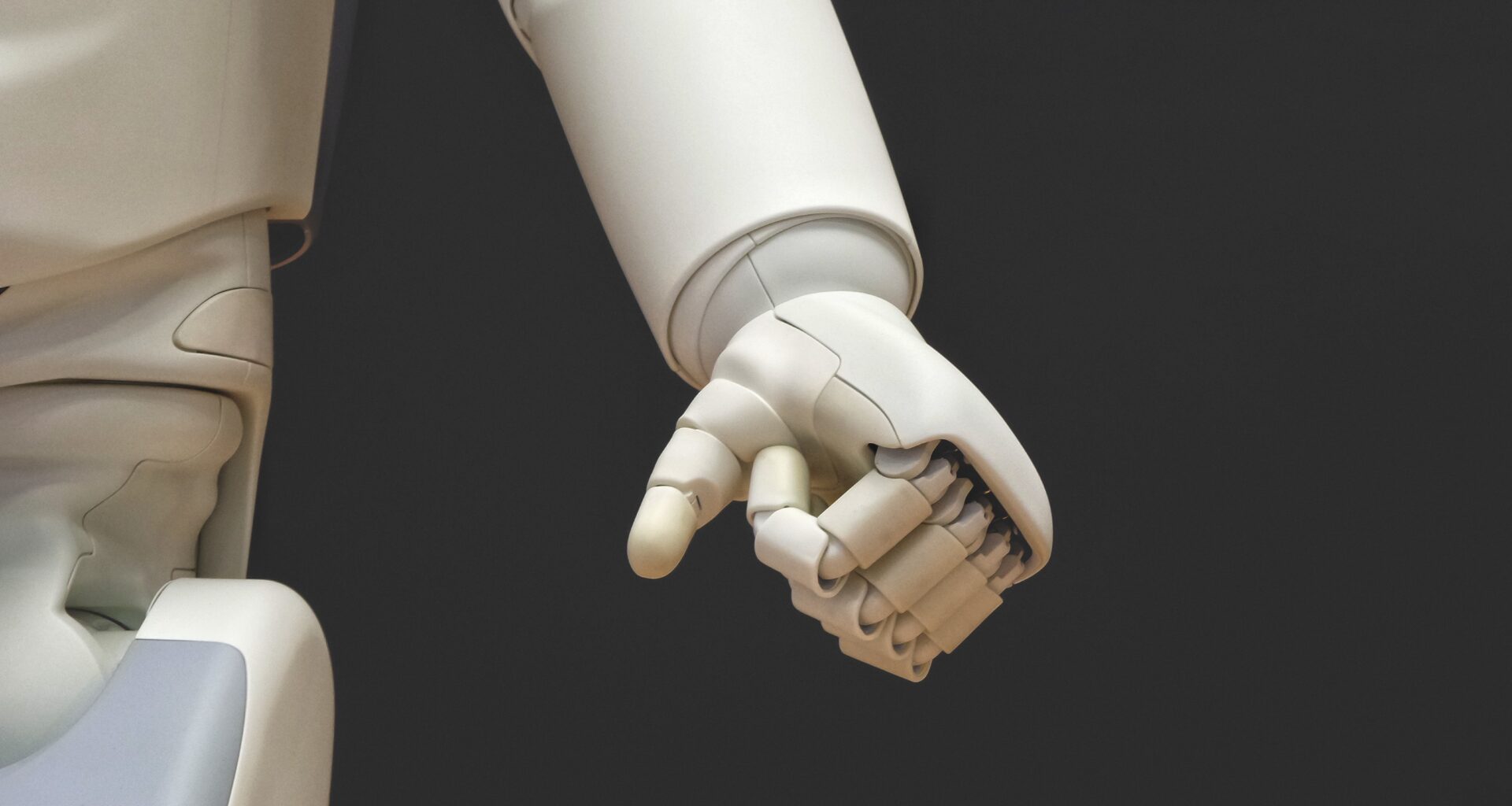

Behind the scenes at the APEC summit, however, US officials hope to strike up a dialog with China about placing guardrails around military use of artificial intelligence, with the ultimate goal of lessening the potential risks that rapid adoption—and reckless use—of the technology might bring.

“We have a collective interest in reducing the potential risks from the deployment of unreliable AI applications” because of risks of unintended escalation, says a senior State Department official familiar with recent efforts to broach the issue and who spoke on condition of anonymity. “We very much hope to have a further conversation with China on this issue.”

Biden’s meeting with Xi this week may provide momentum for more military dialog. “We’re really looking forward to hopefully a positive leaders meeting,” the State Department official says. “We can really understand from that conversation, where our possible bilateral arms control and non-proliferation conversation could progress.”

The US is already leading an effort to build international agreement around guardrails for military AI. On November 1, Vice President Kamala Harris announced that 30 nations had agreed to back a declaration on military AI that calls for the technology to be developed in accordance with international humanitarian law, using principles designed to improve reliability and transparently and reduce bias, so that systems can be disengaged if they demonstrate “unintended behavior.”

The US has been lobbying other nations to join the declaration and will today launch the implementation of the declaration on military AI, which has now been signed by 45 other nations, at the United Nations.

The declaration “advances international norms on responsible military use of AI and autonomy, provides a basis for building common understanding, and creates a community for all states to exchange best practices,” says Sasha Baker, acting under secretary of defense for policy.

The US, China, and the European Union have all launched initiatives aimed at shaping AI regulations. Earlier this month, representatives from many nations came together in the UK to sign a declaration warning about the risks posed by AI. At the same time, every nation with the resources is currently racing to advance AI as quickly as possible.

The military potential of AI has, however, emerged as a key sticking point in an increasingly tangled relationship between China and the US. Many policymakers view the technology as a crucial way for the US to gain an edge over its rival. This potential is a key reason why the US has sought to limit China’s access to advanced semiconductors, to hamper its ability to harness the technology for military ends.

Policymakers who advocate for military adoption of AI also acknowledge that the technology may bring a range of new risks, including the possibility that use of AI increases mistrust between potential adversaries or that malfunctioning systems spark an escalation in hostilities.

“There should be some room to discuss use of AI associated with lethal autonomous weapons systems,” says Paul Triolo, an expert on US-China policy issues at Albright Stonebridge Group, a strategic advisory firm.

Efforts to ban lethal autonomous weapons that target humans have so far stalled in discussions at the UN, but a new resolution, announced this month, may provide more momentum for restrictions.